The Manchester Fly Facility team recently hosted a continuing professional development (CPD) day for a group of Key Stage 3, 4 and 5 science teachers, to showcase their existing lesson packages (and more are in production…). This was an important opportunity for the droso4schools team to explain their resources and gain feedback from a focus group of experienced teachers – namely, what are the lessons like to use? Could they be improved? Most importantly, are they curriculum-relevant?

The Manchester Fly Facility team recently hosted a continuing professional development (CPD) day for a group of Key Stage 3, 4 and 5 science teachers, to showcase their existing lesson packages (and more are in production…). This was an important opportunity for the droso4schools team to explain their resources and gain feedback from a focus group of experienced teachers – namely, what are the lessons like to use? Could they be improved? Most importantly, are they curriculum-relevant?

The day began with a tour of the fly facility, a short activity using microscopes to identify common phenotypic markers used in Drosophila research, and an introduction to the droso4schools programme by academic lead Professor Andreas Prokop, and long-time collaborator Dr Catherine Alnuamaani, a teacher and keen Drosophila advocate from Trinity CoE High School, Manchester. Andreas and Catherine together explained the mutual benefits of using Drosophila as a teaching tool: the benefit for pupils and teachers lies in the fact that Drosophila provides uniquely detailed biology knowledge, delivering concepts, stories and experiments across biology – paired up with human examples to illustrate relevance. Researchers benefit in that students are introduced early on to the power of research with genetic model organisms as a key driver for scientific discovery, and will then hopefully be more open to such research strategies when entering university.

As Catherine highlighted, teaching practicals can become a little monotonous, and the experiments themselves are rarely very exciting. Using a live animal in the classroom puts the “life” back into the life sciences, and encourages pupils to engage with the subject content – Drosophila brings real-world relevance to the curriculum. Not only that, it also provides an opportunity for teachers to develop experimental skills, in a way that is both cost-effective and more interesting than starch-storing potatoes. But what benefit is there for researchers? As Andreas explained, many students who arrive at university to study life sciences, often don’t have much of an interest in invertebrates – they are attracted to applied vertebrate biology and clinically oriented research. Of course, this kind of research is important, but it is fundamental biology which forms the basis on which “translation” can occur. By demonstrating to school pupils the potential scope of fruit fly research, it enhances the chance that those who choose to study the life sciences at university, will have more of an appreciation for the impact of Drosophila research on modern science, and be keen to explore the field themselves.

The itinerary for the day included three full lessons in which the participating teachers took part from the student perspective. Each lesson consisted of a well-structured PowerPoint presentation guiding through the contents, interspersed with short activities and micro experiments. A couple of the participants had been using flies from the facility in their lessons already, mainly as a means of demonstrating genetic crosses; one had even been using elements from the “alcohol lesson” (see below), with great success, for two consecutive years. These teachers reported that students loved having live animals in the classroom, and so they had come to explore other options. The rest of the group were relatively new to the idea of Drosophila as a teaching tool. Some knew how they’d like to use the flies, but weren’t sure where to start. Others were curious, but not sure how successful flies could be as a learning resource, and how easy it would be to source materials.

Being in a classroom full of teachers is something of a surreal experience, but everyone was more than happy to get stuck in, ask questions, work in groups, and contribute to class discussions. The first lesson, concerning the fundamentals of nervous system organisation and function (“Principles of the Nervous System”), gave the participating teachers their first opportunity to work with live flies, through a series of micro behavioural experiments involving the shaking of epileptic flies into seizure (an experiment that is used to illustrated wiring principles and the mechanism of nerve impulses), and another causing transient paralysis of shibire mutant flies (which involves keeping vials of flies under your armpits for five minutes … always popular with pupils!).

Lesson two (“From gene to enzyme to evolution: using alcohol metabolism to illustrate fundamental concepts of biology”) is a fantastic revision lesson to use before the A-level exams, lining up a broad range of specifications, from gene expression to enzymes to evolution, into a consistent story. It contains a particularly hands-on practical, studying enzymatic reactions using the dissection of Drosophila larvae followed by a 5 minute staining reaction, which was very well received by the participants. This practical also provides a means to demonstrate the potential impact alcohol consumption can have on health, providing opportunities to discuss this topic most relevant to students of that age.

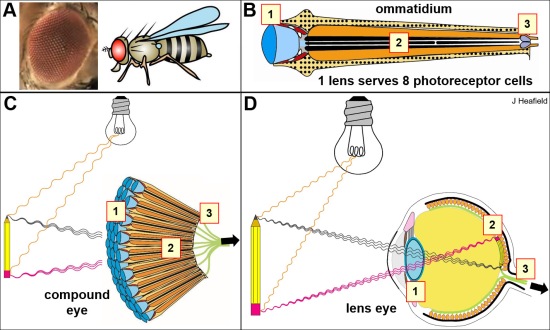

The third lesson (“Our vision: understanding light and light perception”) was of particular interest to me, as I had worked on its experimental component during my placement at the Manchester Fly Facility. I used the fact that flies are attracted to light (an innate behaviour called positive phototaxis) to test responses to different wave-lengths, using normal and sevenless ‘colour blind’ flies. This experiment is particularly effective, as taxis behaviours are simple automatic responses to a given stimulus, and therefore easy for pupils to identify and observe. I had some great feedback from the teachers, a number of whom commented on the short fly behaviour video, and how easy it would be for pupils to engage with – which was very rewarding! Most importantly, it was later highlighted that the observation of taxis behaviours is now a compulsory part of the AQA A-Level biology practical syllabus – so if any teachers are reading this, it is worth taking a look at this lesson!

A brief overview of another lesson (“The climbing assay: learning data analysis through live experiments with fruit flies”) was received with particular enthusiasm by everyone and sparked imaginations. This lesson makes use of a climbing assay that compares motor activities of young versus old flies to perform statistical analyses. Many of the teachers seemed quite excited to use this particular lesson with some of their younger (KS3) classes, as well as for the GCSE and A-Level students, as it is so easily translatable. Not only would it be straightforward to teach, but all agreed it would be a great way to engage pupils with what is traditionally not the most interesting part of scientific methodology.

To complement the lesson sessions, Sanjai Patel (manager of the Manchester Fly Facility) provided a short masterclass on basic fly handling and care techniques, in which teachers were given flies and had to tip them over into fresh vials. Everyone seemed to get the hang of it quite quickly, and there were hardly any escapees! Finally, teachers were given a “guided tour” through the facility’s droso4schools website (describing the resources and given additional support information), the teachers’ section of the Manchester Fly Facility website, and the figshare.com repository providing all the teaching resource files for download.

At lunch and during the concluding session of the day, there was a chance to consolidate the day’s information, reflect on the lessons, share thoughts and opinions on the ease of using Drosophila as a teaching tool, and provide feedback to the team. It was very inspiring, and also in many ways reassuring, to talk to teachers from different schools and areas, who were similarly passionate about their career choice, and their roles as science advocates. During the discussion, a number of excellent ideas were raised, and it was great to see how enthusiastic all the participants were about the project, and how keen they were to get back in the classroom and try the lessons for themselves! Positive feedback included:

- how easily adaptable all the resources were – images, lessons, and other materials can be downloaded and utilised separately, or in whatever combination is convenient.

- how easy it was to link the Drosophila practicals to current research, providing that real-world edge so often missing in everyday lessons.

- that the lessons provide an excellent resource for pupils practicing the new synoptic essays (a synoptic essay assesses a pupil’s ability to demonstrate and apply their understanding of a topic, using a variety of examples on a given theme); often, this additional knowledge is obtained outside of the classroom, through private study.

- that the depth and breadth of information available about Drosophila is easy to incorporate as “additional” information into revision lessons.

An area for improvement mentioned by some of the participants, was that there was something of a “language barrier”, i.e. the differences in basic terminology used in research, compared to that used in schools. Other barriers mentioned were the complex technicalities of the GSCE and A-level curriculum. As a potential solution to tackle these barriers, it was suggested that an experienced teacher could become involved with the droso4schools programme, to “fine-tune” the resources. As it was put by one participant: “You are almost there, but it now needs someone with A-level experience to fully adapt them for school use”.

Overall, the day was very uplifting, and all seemed to head for home brimming with new ideas – be it how to introduce flies to their lessons, or how to further improve available resources. Science lessons should never be boring – neither for pupils nor for teachers. Introducing Drosophila to the classroom provides a new and exciting way to observe science in action, in a way which is convenient, affordable, and manageable. Enthusing pupils about the possibilities presented by research with this powerful invertebrate could also help to inspire a new generation of fundamental life scientists and, who knows, maybe even a few more Nobel Prize winners!

Charlotte Blackburn